Protect Privacy by Overhauling the Protect America Act

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary

Hearing Regarding Warrantless Surveillance and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA): The Role of Checks and Balances in Protecting Americans’ Privacy Rights

September 5, 2007

2141 Rayburn House Office Building

Chairman Conyers, Ranking Member Smith, and Committee Members, on behalf of the ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ (‚Äú¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚‚Äù), America‚Äôs oldest and largest civil liberties organization, its 53 affiliates and hundreds of thousands of Members, we write to share our views with the Committee regarding the recently enacted Protect America Act, Pub. L. 110-55, and legislation to replace that Act. Because ¬ß 6 of the Protect America Act causes the Act to sunset if not reauthorized or replaced within six months, the ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ recommends that this Committee allow the Act to expire. Alternatively, should Congress feel compelled to legislate, Congress should replace the Act with a full scale revision that respects the letter and spirit of the Fourth Amendment with regards to intercepting U.S. persons‚Äô communications.

Congress must also vigorously resist legislative attempts to grant retroactive immunity to government employees and telecommunications companies and their employees for facilitating criminal and unconstitutional wiretapping. Absolving these individuals and companies of their violations of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act’s (“FISA”) will encourage future lawlessness and interception of communications outside of FISA. Ultimately, extinguishing liability – especially while litigation is proceeding – will prevent U.S. citizens from vindicating their constitutional, legal and contractual rights as customers of the telecommunications companies.

Neither the Protect America Act, nor S. 2011, authored by Sen. Carl Levin (D-MI) and Intelligence Committee Chair, Sen. John D. Rockefeller, sufficiently protect the privacy of communications of innocent U.S. persons. Any legislation replacing the Protect America Act must reintroduce privacy protections into FISA’s treatment of communications intercepted between U.S. persons and persons reasonably believed to be outside of the United States.

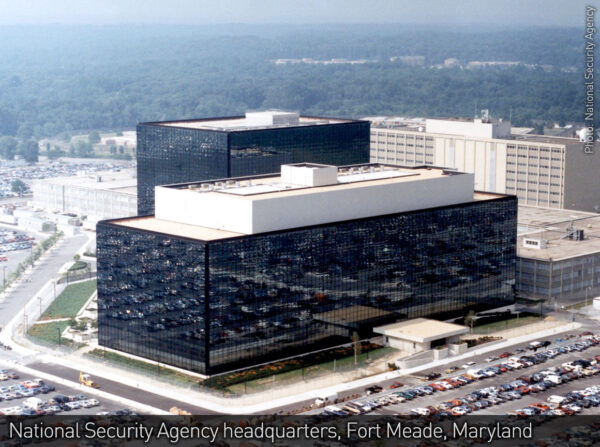

In passing the Protect America Act, Congress legislated in the dark and should not do so again. Despite repeated requests for documents, testimony and briefings regarding the illegal, warrantless wiretapping conducted at the President’s bequest, Congress has to date been utterly stymied in conducting meaningful oversight over those illegal acts. The White House has flouted Congressional subpoenas and deadlines for the provision of documents related to that warrantless wiretapping. The end result is that Congress has effectively been prevented from conducting oversight regarding surveillance conducted on U.S. soil since September 12, 2001. In essence, Congress has been all but eliminated as an independent check on abuses by the President and the National Security Agency (“NSA”). No amendments to FISA should be made permanent until Congress and the public receive answers about what surveillance activities have been conducted over the last six years and the legal basis for those programs. This Committee should hold extensive public hearings regarding the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping and the telecommunications companies’ facilitation of that illegal wiretapping. Information regarding this illegal activity to determine how the Administration ignored the clear mandates of FISA should be forthcoming prior to the enactment of any new legislation. After all, any Congressional effort to carefully draw the statutory lines between permissible surveillance to prevent acts of terrorism is meaningless should this, or a future, Administration choose to ignore or circumvent FISA’s mandates and limitations. Further, information regarding how the authorities provided for in the Protect America Act are being interpreted and operationalized by the NSA should be shared with Congress. To facilitate Congress’ legislative efforts, the NSA should be required to articulate with specificity the problematic aspects of the prior statutory scheme and whether the Protect America Act responds to those intelligence concerns.

The ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ also recommends that Congress codify a FISA regime that increases the privacy protections for U.S. persons‚Äô communications as the level of intrusiveness of intercepts of those communications increases. If content is acquired and/or reviewed, particularly where probable cause has not been developed to investigate a U.S. persons‚Äô communications, the government‚Äôs burden of protecting that communication should be increased, and commensurate limitations should be placed on the use or dissemination of that communication to ensure compliance with the Fourth Amendment. Additionally, meaningful judicial review of the NSA must be built into any legislation so that the court may act to ensure the privacy of U.S. persons‚Äô communications. Only the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (‚ÄúFISC‚Äù) can insist that surveillance is targeted to individualized intercepts. Court review is also essential so as to force the NSA and Department of Justice to comply with the letter and spirit of any new law enacted.

II. Analysis of the Protect America Act and S. 2011

President Bush enacted sweeping revisions to FISA on August 5, 2007 by signing into law the Protect America Act. The Act was signed just two days after final passage by the U.S. Senate and one day after final passage by the U.S. House of Representatives. Director of National Intelligence McConnell allegedly lobbied heavily and personally for the Act‚Äôs passage, briefing more than 200 Members of Congress on the NSA‚Äôs purported need to close an intelligence gap. This rush to legislate led to a substantially overbroad law that does not appear to provide the type of narrowly-targeted expansion of surveillance authority McConnell claims to have sought. Rather, the Act appears to have eroded Americans‚Äô privacy protections for their e-mails and phone calls to and from foreign-based persons ‚Äì including U.S. citizens living, working or traveling abroad ‚Äì in a tidal wave of over-reaching legislative language. The ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ calls upon Congress to reverse this sea change in the laws governing surveillance by the U.S. government of U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents.

The Protect America Act turns the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on its head.[i] It eviscerates privacy protections for U.S. persons’ communications and does great damage to the Fourth Amendment’s protections by:

(i) expressly permitting non-targeted, warrantless mass acquisition of U.S. persons’ communications with foreign-based communicants by defining such communications as outside of the definition of FISA-protected “electronic surveillance”;

(ii) failing to require the NSA to demonstrate that they have probable cause to believe one party to the communication is a terrorist or foreign power before intercepting U.S. persons’ communications;

(iii) eliminating requirements that factual predicates for surveillance be listed with specificity such as the “facilities, places, premises, or property at which the acquisition of foreign intelligence information will be directed;” and

(iv) implicitly permitting the limitless warehousing and subsequent data mining of both the metadata regarding those communications and the content of the communications themselves.

First, the Act states that all intercepts of communications – both e-mail and phone calls – between any person the government “reasonably believe[s]” is located outside the U.S. and anyone within the U.S. are exempt from the definition of Fourth Amendment-protected electronic surveillance. Protect America Act, Pub. L. 110-55 at § 105B(a). Thus, for the first time, FISA: (i) permits the mass acquisition of U.S. persons’ communications, (ii) eliminates any requirement that the government target its acquisition to acquire only certain persons’ conversations; and (iii) eliminates the requirement that a judge approve those interceptions. Now, if the government is directing its surveillance at foreign-based communicants it may sweep up the conversations of U.S.-based persons. FISA previously required the government to establish reasonable suspicion or probable cause to obtain, keep and utilize the communications of U.S. persons that were inadvertently acquired. Second, the Protect America Act eliminates any requirement that the NSA, in obtaining a general warrant, provide facts to target the interceptions to specific facilities, places, premises or property. Id. at § 105B(b). In short, the FISC no longer plays a meaningful role – one that it had played effectively since 1978 – and it can no longer provide judicial oversight given the powers granted to the NSA in the Protect America Act. This amendment to FISA essentially establishes a system of surveillance solely dictated and controlled by Executive Branch fiat without the independent review by the judicial branch. Further, the Act essentially eliminates judicial review of DOJ and NSA activities by the FISC. The end result is a cosmetic patina of judicial review without providing the FISC with substantive authority to halt or modify improper intercepts. Finally, the Protect America Act permits continued warrantless surveillance of a person, account or facility – even when it becomes clear that the subject of surveillance will have repeated contact with a U.S. person.

All of these constitutional and policy failings are only exacerbated by the fact that the Protect America Act allows the government to retain, use and disseminate the content of or the data about these communications however it sees fit. While supporters of the Protect America Act point to so-called “minimization procedures,” those procedures have never been used on mass, otherwise legalized collection, nor have those procedures ever had a public airing. In effect, the Protect America Act resorts back to “trust us,” and leaves the Administration to its own devices to operate in secret and without any limitation on how to treat U.S. information. Thus, the NSA is now permitted to intercept and utilize communications without minimizing the U.S. persons’ identity and personally identifiable information. Prior to the Protect American Act, personally identifiable information and “header” information identifying a particular U.S. person would have been minimized.

The Act, therefore, erects a geometric increase in the kind and quantum of U.S. persons’ communications that may be intercepted. It is no exaggeration to state that all communications – both e-mails and phone calls – originating from a non-U.S.-based person could be intercepted. Similarly, the communications to people abroad originating from the U.S. also are likely to be intercepted as part of the communications chain. In short, it is likely that all, or substantially all, communications entering or exiting the U.S. will be intercepted. The implications of such a change are profound, likely leading to the acquisition of all communications in the following illustrative scenarios:

(i) communications to U.S.-based businesses from their foreign-based subsidiaries or business partners/clients;

(ii) calls and e-mails to U.S.-based parents of high-school, college, and university students participating in “study abroad” programs;

(iii) calls and e-mails between missionaries and their religious sponsor churches, mosques and synagogues in the U.S.;

(iv) e-mails and calls from any U.S. citizen travelling outside of the U.S. on vacation; and

(v) purely domestic calls and e-mails between U.S. persons that are routed through foreign countries, such as Canada, simply for ease, cost-savings, or network efficiency.

Now, the mass interception of foreign-to-U.S. communications is permissible due to the evisceration of Fourth Amendment-based statutory requirements that mandated the targeting of, interception and judicial approval of individualized surveillance.

The Protect America Act also implicitly authorizes mass warehousing and limitless data mining of the communications of U.S. persons intercepted. The Act states that the government may engage in “acquisition [of] foreign intelligence information” from a “custodian” either as the communications are “transmitted or while they are stored . . . .” Id. at § 105B(a)(3). In essence, the Act facilitates the application by the NSA for a general warrant for a group of individuals and their communications, no matter whether a U.S. person’s communications are swept up. Because Congress failed to limit the types of data mining that may occur, or prevent data mining of the metadata concerning the communications, we can expect the application of link analysis data mining to attempt to establish the relationship between a foreign-based communicant and the U.S. person with whom they communicate, even if the contact is casual, incidental or accidental. Thus, an innocent U.S. person whose communications are intercepted because they received a phone call or e-mail from a person reasonably believed to be located overseas could come under government suspicion simply because they were sent an e-mail or received a phone call.

The failure of Congress to limit the data mining of either the metadata concerning the communications or the content of those communications is likely to have profound legal and practical consequences for innocent U.S. persons. The Act does not limit the NSA’s ability to interpret the communications intercepted, thus innocent U.S. persons’ communications could be misinterpreted because the data mining of the content of those communications detects the presence of some code word. The implications for innocent U.S. persons wrongly drawn into this web of government suspicion are heretofore unknown. Certain questions naturally arise from this lack of legal limitation:

(i) will innocent U.S. persons’ exercise of legally or constitutionally guaranteed rights and privileges be limited?;

(ii) what redress, if any, will innocent U.S. persons have when their communications are misinterpreted?;

(iii) how will an innocent person who is wrongly suspected recover his or her good name and reputation?; and

(iv) will the friends, families and associates of the wrongly suspected U.S. persons also come under suspicion? If so, are there any limits to the concentric rings of communicants (i.e., how many degrees of separation removed from the foreign-based communicant) the government will draw into this burgeoning web of suspicion?

The Protect America Act’s revisions of FISA also render the longstanding law unrecognizable by virtually eliminating the role of telecommunications providers as independent guarantors of their customers’ privacy under this new mass communications acquisition scheme. The Act substantially eliminates the ability of the telecoms to resist facilitating the interception of U.S. persons’ communications. As originally drafted, FISA placed the telecoms in the shoes of their customers and permitted the telecoms to go to court to resist an allegedly improper FISA intercept application on a customer’s behalf. The Protect America Act eviscerates this third-party guarantor role. It permits the NSA to demand that telecoms facilitate interception. Id. at § 105B(e). Should a telecom resist such a directive, the NSA may obtain a court order compelling facilitation. Id. at § 105B(g). Failure to comply with that court order is punishable with a finding of contempt of court. Id. Although the Act sets forth procedures for a telecom to challenge a directive, the streamlining of the FISA application – such as the elimination of the requirement that the NSA provide specific targeting facts – prevents attorneys for any telecom from having certain pre-existing avenues to challenge the legal sufficiency of a mass acquisition directive. Further, the FISC must review any ex parte, sealed submissions regarding the interception, which lessens the likelihood that a telecom could successfully resist such an interception directive. Id. at § 105B(k).

In addition, to reduce the telecom industry’s resistance to facilitating mass communications interception, the Protect America Act provides significant financial inducement to the telecoms. Pursuant to the Act, the telecoms are compensated “at the prevailing rate” for “providing information, facilities, or assistance” to aid the government’s wiretapping. Id. at § 105B(f). Thus, the Act guarantees that wiretapping facilitation remains profitable for the telecoms. More importantly, to further erode telecom resistance to this massive wiretapping expansion, the Act grants the telecoms seeming absolute prospective immunity for wiretapping of e-mails and phone calls pursuant to the Act. Id. at § 105B(l).

The reporting requirements of the Act do not guarantee that Congress, much less the media or the public, will have sufficient information about wiretapping permitted under the Act to judge its efficacy or the NSA’s compliance with the Act. The Attorney General of the U.S. is only required to brief the four lead Congressional Committees – the House and Senate Intelligence and Judiciary Committees – semiannually. That report need only provide a “description . . . of incidents of non-compliance by an element of the Intelligence Community with guidelines or procedures established for determining that the acquisition of foreign intelligence [pursuant to the Act] concerns persons reasonably believed to be outside the United States.” Further, the report only must list the number of certifications issued by the Attorney General and the number of directives to telecoms to facilitate interceptions during the relevant period. In short, Congress’ failure to require additional information or reporting specificity prevents the provision of information to judge:

(i) whether the Act’s expansion was justified or useful from an intelligence resource perspective;

(ii) whether violations of U.S. persons’ constitutional or legal rights occurred;

(iii) whether the interceptions ordered are targeted in any way to comport with the Fourth Amendment’s requirements; and

(iv) whether and/or what disciplinary action was taken for any violations of any procedural, regulatory, legal or constitutional violations by any NSA or Department of Justice employee.

The Protect America Act also includes a six month-long “sunset” provision, which causes the Act to expire if it is not replaced within six months after the date of enactment (i.e., after February 5, 2007).

The Democrats‚Äô alternative legislative proposal, S. 2011 (the short title of S. 2011 was also the Protect America Act, therefore, hereinafter ‚ÄúDemocrats‚Äô alternative‚Äù or ‚ÄúS. 2011‚Äù), introduced by senior Intelligence Committee Member Senator Carl Levin (D-MI) and Committee Chair John D. Rockefeller (D-WV), failed ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ standards in several important respects. First, the Democrats‚Äô alternative eliminated targeting requirements in language identical to the Protect America Act. S. 2011 at ¬ß 105(B)(b)(2). This allows for the mass acquisition of communications involving at least one U.S. person. Further, the legislation authorized year-long interceptions. Id. at ¬ß 105B(a). Additionally, the Democrats‚Äô alternative would have created a ‚Äúlisten-first-apply-for-a-warrant-later‚Äù procedure authorizing immediate interception of U.S. persons‚Äô communications with persons reasonably believed to be outside the U.S. Id. at ¬ß 105C. Finally, the alternative left the Executive Branch to minimize U.S. persons‚Äô communications through secret Attorney General-issued procedures, and did not require that improperly intercepted U.S. persons‚Äô communications be destroyed. This amendment would have permitted surveillance without any indicia of Fourth Amendment protection in that U.S. persons‚Äô communications could be intercepted and reviewed in the absence of any targeting of the foreign-based communicant and without probable cause or reasonable suspicion to have been developed with respect to the U.S. person.

The Democrats‚Äô alternative was superior to the Protect America Act in two respects, neither of which outweighed the alternative‚Äôs implications for vastly expanded acquisition of U.S. persons‚Äô communications with foreign-based persons. First, S. 2011 would have required court review of the Attorney General‚Äôs certification and application for surveillance. Id. at ¬ß 105B. In contrast, the Protect America Act requires only certification by the Attorney General. Second, S. 2011 would have required the NSA to obtain a warrant from the FISC to continue interception at the point at which the U.S. person became the subject of surveillance. Id. at ¬ß 105B(d). The ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ supports both of these improvements.

III. Recommended Principles for Reforming the Protect America Act

The ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ notes again that Congress is not compelled to pass additional legislation. The effect of not doing so would be to return FISA to the statutory limitations in place prior to enactment of the Protect America Act. The ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ believes that no legislation would be better than the permanent authorization of the Protect America Act or any legislation that substantially mirrors that Act. Further, any grant of retroactive telecom immunity will reward law-breaking and fundamentally undermine the FISA structure by eliminating any arm‚Äôs length distance between the telecoms and the government. In short, should the telecoms be given amnesty for violating the law, AT&T, Verizon and other companies will essentially be functioning as quasi-governmental appendages of the NSA.

In the alternative, should Congress feel compelled to legislate, the ¿œ∞ƒ√≈ø™Ω±Ω·π˚ recommends that this Committee adhere to the following principles in drafting legislation to replace the Protect America Act:

1. Any further legislation must reiterate that FISA is the exclusive means of intelligence gathering on U.S. soil, and the legislation must include automatically triggered consequences for violating this exclusivity. As initially enacted by Congress, the exclusivity of FISA was unambiguous. This new exercise in defining the lawful extent of surveillance authorities will be useless if the resulting legislation can be ignored. We further recommend that any new legislation state explicitly that the Authorization for the Use of Military Force in Afghanistan and Iraq do not authorize any surveillance outside FISA. Additionally, we recommend that the NSA be required to report to Congress repeatedly on its implementation of any new surveillance activities conducted pursuant to FISA.

2. Interceptions of U.S. persons’ communications within the U.S. should continue to be included within, and, therefore, protected by the definition of “electronic surveillance.” The Protect America Act’s seeming elimination of this protection should be repealed.

3. Collection and isolation of the particular communications sought by the government should be conducted by the telecommunications industry itself – the government should not be given direct and unfettered access to telecommunications infrastructure. We are concerned that the Protect America Act appears to allow the government to “sit on the line” and scoop up all communications and sort through them later. Instead, the government should receive only the information it is authorized to intercept by law.

4. The FISC must play a meaningful role in ensuring compliance with the law. First and foremost, electronic surveillance should be authorized by the FISC through the issuance of an individualized warrant based on probable cause. This oversight should include, where possible, prior and, always, regular judicial approval and review of surveillance based on full disclosure about what information is to be sought, whose communications will be collected, how it will be gathered and how content and other data in communications to and from the United States will be handled. The Court must also have regular access to information about how many U.S. communications are being collected and the authority to require court orders when it becomes clear that a certain program or surveillance of a target is scooping up communications of U.S. persons.

5. Under any new amendment to FISA established in your legislation, when the government intercepts a communication to which a person in the U.S. is a party, there should be a presumption requiring the NSA to immediately destroy that communication unless the NSA documents that it has reason to believe that the communication reflects an immediate threat to life or limb. All public FISA legislation has been deficient in that it has lacked a presumption of destruction of the improperly intercepted communications of U.S. persons. Without such a presumption, the Administration’s secret “minimization” procedures will be all that govern U.S. communications. Congress has the authority – and the responsibility – to explicitly define how these communications are treated, and should no longer defer to the Executive branch’s unknown policies. If the programs are truly directed at people overseas, this should be noncontroversial.

6. Once the government has reason to believe that there is a substantial likelihood that a specific account, person or facility will have contact with someone in the United States, the government should be required to return to the FISC to obtain a court order for continued surveillance of that account, person or facility. Reliance on the FISC will help ensure the privacy of U.S. persons’ communications.

[i] The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution provides in pertinent part that “no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be search, and the persons or things to be seized.”