On April 29, 2014, Clayton Lockett was scheduled to die by lethal injection at the hands of the State of Oklahoma. Under a state law that requires public witnesses to all executions, 12 journalists gathered to observe his death.

They never saw it.

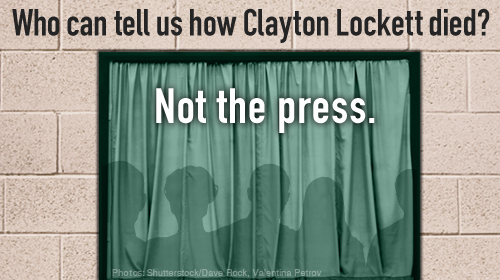

Before the scheduled execution, the reporters were ushered into a media room where a glass partition, covered by a "viewing blind," separated them from the execution chamber. When the blind opened, Clayton Lockett lay before them strapped to a gurney. He had already been in there for almost an hour, getting poked with needles until a member of the execution team ÔÇô of unknown training and background ÔÇô finally set an IV line in Lockett's femoral vein, near his groin. Preliminary findings suggest this femoral IV played a role in Lockett's prolonged and torturous execution. Since there were no witnesses, we have only the state's account of how properly these IV procedures were carried out.

But that's certainly not all that journalists were barred from seeing. Right after the blind was raised, the warden announced that the injection process was to begin: First came the drug intended to render Lockett unconscious. Seven minutes later, at 6:30 p.m., a doctor in the room checked Lockett for consciousness; he was awake. At 6:33 p.m., he checked again; the claims the "offender was unconscious." So Oklahoma began the process of injecting Lockett with the second drug (a paralytic), and the third drug, intended to induce cardiac arrest.

But Lockett most certainly didn't remain unconscious while the execution team administered these drugs. Multiple media reports document that Lockett began to moan and writhe on the gurney in clear distress. And how did state officials respond? They lowered the blind. At 6:42 p.m., at the very most critical moment of the execution proceeding, the state opted for secrecy. Once there was unavoidable evidence ÔÇô visual and audible ÔÇô that the lethal injection was cruel and unusual, the media was locked out. The journalists were left staring at a blank blind, able to hear ÔÇô but not verify ÔÇô sounds of struggle and suffering coming from inside the death chamber.

They never saw anything else.

We now know that Lockett died at 7:06 p.m., long after the media's access was shut down by the state. As to what happened in those fateful 25 minutes, we have only the words of state officials, and those words themselves beg some questions. The the state "lawfully carried out the sentence of death," while the head of the state Department of Corrections ÔÇô who runs executions in the state ÔÇô the execution was formally called off 10 minutes before Lockett was "pronouncedÔÇŽdeceased." Once the state is no longer "executing" someone, their duty shifts to one of providing medical care, but there are certainly no reports that they attempted to resuscitate Lockett. Assuming they didn't, the process was, and remained, an attempt to kill him. A process the press had every right to witness.

Because the press and public were literally and figuratively shut out of witnessing the process, we may never get a reliable answer. But here's where there's no question: For over 20 minutes, Clayton Lockett lay there dying in the dark. The assembled reporters were deprived of the right to observe a critical government proceeding, and by extension the public was denied the right to receive a full account of how Oklahoma administers capital punishment, warts and all.

Both death penalty supporters and opponents should be able to agree that the most extreme use of state power should absolutely not occur in the shadows. As the Supreme Court , "The protection given speech and press was fashioned to assure unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people."

As citizens, we can't complete that duty if the government only offers us selective information, editing out all the ugly parts. That why we brought a lawsuit today asking the court to stop the state of Oklahoma from using the execution shade like a Photoshop tool.

It isn't transparency when the government shines a light only on the things it wants us to see.

Learn more about freedom of the press and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .