Black and Blue: The All-Too-Often Toxic Relationship Between Communities of Color and Law Enforcement

Twenty-five years ago, Director Spike Lee released the film "Do the Right Thing" which illustrated with startling realism the racial tensions and uneasy relationship between police and the communities of color in Brooklyn's Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood. The film's message about the need to alter the fraught relationship between communities of color and law enforcement has assumed renewed importance with the events surrounding the tragic killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson this summer.

One clear message that emerges is that the decision by the St. Louis County Grand Jury not to indict Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson for that killing cannot be the final word in the discussion about the all-too-often toxic relationship between communities of color and law enforcement.

As an initial matter, the Department of Justice can still conduct an exhaustive investigation about Brown's shooting as well as looking at the broader question of unfair repressive practices in the Ferguson Police Department as a whole. But even though the current focus on police practices was triggered by the Brown shooting, the events that occurred in its aftermath have demonstrated that the underlying problem is neither new nor limited to the shooting of Brown or to the city of Ferguson.

Similar concerns about the use of deadly force in communities of color have appeared throughout the country. The following list is long and by no means exhaustive.

In Staten Island, New York, Eric Garner died after being placed in an illegal choke hold while being arrested for selling loose cigarettes. John Crawford, an African American man, was shot while speaking on his cell phone and holding a toy gun in the toy aisle of a Walmart in Ohio – an open carry state. Milton Hall, a 49-year-old man with mental illness, was surrounded by eight police officers and a police dog and shot and killed in a hail of 46 shots, even though he was armed only with a pen knife and presented no immediate threat to anyone. Levar Jones was shot by a South Carolina State Trooper while reaching into his car to comply with an order to provide his license in a supposed investigation of a seat belt violation. In Oakland, a handcuffed Oscar Grant was shot and killed while laying face down in a Bart station. These and numerous other incidents suggest the existence of a broader systemic problem that demands investigation regardless of the ultimate outcome of the investigation of Officer Darren Wilson.

Spike Lee ended his landmark movie with a dedication to the families of black New Yorkers killed in incidents in which the specter of race loomed large. Included in the list were Eleanor Bumpurs, Michael Griffith, Arthur Miller, Edmund Perry, Yvonne Smallwood and Michael Stewart" all of whom except Michael Griffith died at the hands of police officers.

Although those names may be unfamiliar to a younger generation, they are a reminder of the persistence of a problem that existed long before Spike Lee's movie and, sadly, appears to continue unabated up to the present. Like all good movies, Lee's movie continues to speak to us in part because it is well-made, but unfortunately, it's timeliness is also due to the fact that the problems that it documented have not changed.

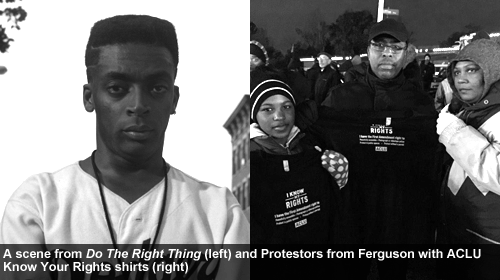

If there is a silver lining in the tragic cloud that has surrounded Ferguson, it is that it has prompted organizing and discussions about the larger issues of the improper use of force against communities of color, communities that ask nothing more than to be provided the same protection and appreciation of their humanity as is guaranteed by laws and the Constitution.

It would be sad if that momentum were brought to a halt by the lack of an indictment in Ferguson and we found ourselves, 25 years from now, substituting a whole new list of names from locations across the country, for the ones immortalized in Spike Lee's film.

Learn more about racial justice and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .