In cases as divided and important as the marriage cases, it is almost always difficult to get a good sense of how the justices will rule just from listening to the oral arguments. But I came away mostly hopeful from Tuesday's oral arguments before the Supreme Court in Obergefell v. Hodges, the consolidated cases from four states that will decide whether same-sex couples have the freedom to marry nationwide.

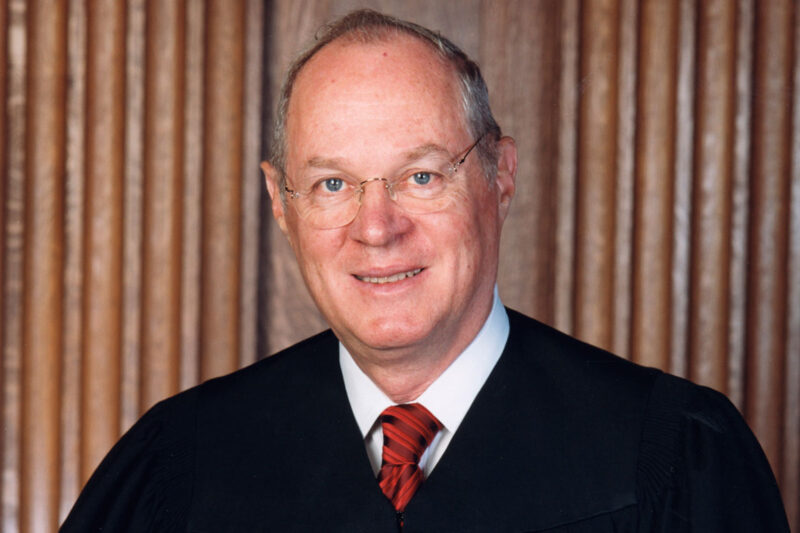

The reason I'm optimistic is simple: Justice Anthony Kennedy, the court's perpetual wildcard, said a lot of reassuring things about marriage equality during oral argument.

1. Journey from Lawrence to marriage. Justice Kennedy noted that approximately the same amount of time elapsed between the court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down racial segregation in the public schools in 1954, and Loving v. Virginia, which struck down bans on interracial marriage 13 years later, and between Lawrence v. Texas, which struck down criminal sodomy laws in 20o3, and these cases about the constitutionality of bans on marriage for same-sex couples 12 years later. That suggests he may think the time is right.

It also suggests that he rightly thinks of the court's decision in Lawrence, which he wrote, as the Brown of the gay rights movement. If that's how he thinks of Lawrence, it seems less likely that he'd be prepared to tarnish his legacy and stop the evolution of his conception of liberty short of marriage.

2. Dignity of marriage. Yesterday, Justice Kennedy reaffirmed his view that marriage is about dignity and echoed his statements in Windsor that the Constitution protects the equal dignity of gay people. Dignity came up when the states' lawyer, John Bursch, made the surprising assertion that marriage has never been a "dignity-bestowing" institution.

"I don't understand this ãnot dignity bestowing,'" Kennedy replied. "I thought that was the whole purpose of marriage." If that wasn't enough, Kennedy also said, "It's dignity bestowing, and the [gay couple petitioners] say they want to have that ã that same ennoblement," as well as, "Many states would be surprised [that marriages] are not enhancing the dignity of both parties. I'm puzzled by that."

It was a tone-deaf moment for Mr. Bursch, who should have known how central the concept of dignity is to Justice Kennedy and his view of the liberty that the Constitution protects. In a case where everyone on both sides went in presuming that Justice Kennedy was the primary audience, one wonders what Mr. Bursch was thinking.

3. Noble purpose of marriage. When the states' lawyer suggested that voters who enacted the marriage bans wanted to prompt married couples to commit primarily to their children, rather than just to each other, Justice Kennedy pushed back, saying, "But that, that assumes that same-sex couples could not have the more noble purpose [of committing to their children], and that's the whole point. Same-sex couples say, of course, we understand the nobility and the sacredness of the marriage. We know we can't procreate, but we want the other attributes of it in order to show that we, too, have a dignity that can be fulfilled."

4. Concern for children. Justice Kennedy noted that the marriage bans make it more difficult for same-sex couples to adopt children, and said "I think the argument [about children] cuts quite against [the states]." He also stated flat-out that the states' suggestion that only biological parents can bond with their children is wrong, recognizing the reality that many children are raised by adoptive parents, including gay people.

5. Skeptical about harm to traditional marriage. Justice Kennedy also challenged the states' argument that letting same-sex couples marry would harm "traditional" marriage. He asked how such a concern could be "some kind of rational or important" reason for excluding same-sex couples from marriage. And note his use of "rational or important," which caught the attention of many advocates in the courtroom, since "rational" is the language of the lowest level of constitutional review, whereas "important" is part of more searching judicial scrutiny, which is something we are hoping to get for sexual orientation classifications out of the Obergefell decision. This could be a clue that Justice Kennedy may be ready to make the standard more explicit.

6. Concern about states' narrow focus on procreation. Finally, Justice Kennedy seemed concerned about the states' focus on procreation as the primary and even sole purpose of marriage. When the states' lawyer tried to wriggle out of answering a question from Justice Kagan about that, Justice Kennedy pushed for an answer, suggesting that he, too, is perturbed by that narrow focus.

But it wasn't all good, of course. Two comments from Justice Kennedy unsettled me.

At the beginning of the argument, he said that the word that comes to his mind as he thinks about these cases is "millennia," As in the thousands of years of traditional marriage between a man and a woman, contrasted to ten years of experience with marriage of same-sex couples. Later in the argument, Justice Kennedy suggested that the social science about the development of children raised by gay people is too new to tell us whether the kids do okay, and that the court should disregard it. It was quite frustrating to hear that sentiment from him, when it's just wrong, and we've tried so hard to communicate fairly the consensus among child development experts.

Of course, comments at oral arguments are not always reliable guides to how the justices will vote in the end. But the combination of these remarks, Justice Kennedy's prior decisions on gay rights, and the evolution in the country around LGBT rights more generally make me optimistic that a lot of wedding bells are going to ring out come June.