Back in 2007, Reps. Brad Miller (D-N.C.) and James Sensenbrenner (R-Wisc.) to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), Congress's watchdog over the federal government. As the two top members of the Subcommittee on Investigations and Oversight, the two congressmen were worried that the FBI had been covertly reviving Total Information Awareness, a military research and development data-mining program killed in 2003 because of privacy concerns.

The FBI's effort, according to Justice Department documents the congressmen reviewed, would use the tools of "bulk data analysis, pattern analysis, trend analysis and other programs" to "greatly improve efforts to identify ŌĆśsleeper cells.'" The hub for this counterterrorist data-mining would be the newly proposed National Security Analysis Center (NSAC), which would combine multiple federal databases and private data from aggregation companies.

The resulting database, the congressmen discovered, would be monstrous in scope. "Documents predict the NSAC will include six billion records by FY2012," they wrote. "This amounts to 20 separate ŌĆśrecords' for each man, woman and child in the United States." And let's be clear here, that's 20 separate records sitting in an FBI database on each U.S. person without any suspicion of wrongdoing.

A year later, Congress pulled funding for the NSAC after the FBI tried to shake off oversight by refusing to give GAO auditors access to the program. But the program lived on. This year, the Justice Department's Inspector General that the FBI's Foreign Terrorist Tracking Task Force had simply "incorporated" the NSAC and its datasets into its own.

Lesson: big data won't be denied.

Yet the allure of big data is based on a faulty premise: If the government can only develop the right algorithm, then out of the multitudes of data points, dots will get connected and terrorists will be revealed. The problem: there is no empirical evidence to back up such science-fiction fantasies.

In 2008, the National Research Council (NRC), funded by the Department of Homeland Security, into counterterrorism data-mining. Its conclusion didn't inspire confidence. "Automated terrorist identification," according to the study, "is not technically feasible because the notion of an anomalous patternŌĆöin the absence of some well-defined ideas of what might constitute a threatening patternŌĆöis likely to be associated with many more benign activities than terrorist activities." In other words, agents and analysts would be inundated with false alarms and irrelevant data that distracted them from real threats.

Events have proven the NRC correct.

On April 15 of this year, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev allegedly placed two pressure cooker bombs near the finish line of . The resulting explosions killed three people and caused over 250 casualties. In the manhunt that followed, the brothers allegedly shot and killed another police officer before Tamerlan died in a gunfight with police in the early morning hours of April 19 and Dzhokhar was taken into custody by police later that evening.

It wasn't the first time Tamerlan had come to the attention of law enforcement.

Two years earlier, the FBI's Boston Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) conducted a three-month "assessment" of Tamerlan Tsarnaev after receiving a March 2011 warning from the Russian government that he had developed radical views and planned to travel to Russia to join "underground" groups. The FBI concluded Tamerlan wasn't a threat and closed the assessment in June 2011. In early 2012, Tamerlan left for Russia. The FBI, despite the warning from the Russian government that he traveled to meet with extremist groups, did not reopen its investigation into Tsarnaev upon his departure or his return to the United States six months later. The FBI had also the Boston Police Department of Tsarnaev's trip, according to its Commissioner, Edward Davis.

The question instantly became why?

While any of the Boston police officers on the JTTF could have accessed Tamerlan's information on the FBI database all JTTF members have access to, Special Agent in Charge Richard DesLauriers , he hinted at another problem. "In 2011 alone, the Boston JTTF conducted approximately 1,000 assessments," he said, "including the assessment of Tamerlan Tsarnaev, which was documented in the Guardian database." The New York Times 1,000 assessments constituted "a workload that made it unlikely that each assessment could get close attention from every task force member."

What the FBI or Times failed to mention, however, is that assessments are a dubious investigative authority whereby agents can investigate people without any evidence they've committed or are about to commit a crime. By failing to establish any suspicion that someone has done something wrong before opening an assessment, FBI agents create more work and more false leads for themselves. In between 2009-2011, the FBI performed 82,000 assessments. Less than 3,500 of them warranted further investigation.

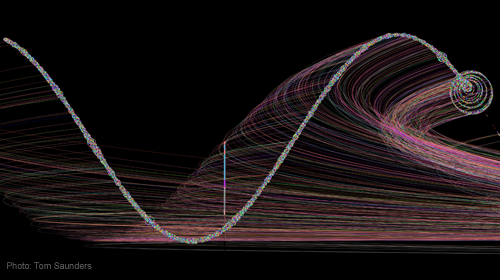

As Unleashed and Unaccountable makes clear, there are many more examples of legitimate threatsŌĆöDavid Headley, Carlos Bledsoe, and ŌĆöthat have fallen through the cracks despite the FBI's increased data collection activities and expanded investigative powers, like assessments, that require agents to devote scarce time and resources to investigating people against whom there is no evidence of wrongdoing. Finding the miniscule number of terrorists hiding among billions of people just going about their day is invariably likened to finding a needle in a haystackŌĆöa nearly impossible task. The answer to this problem, according to the FBI and other intelligence agencies, is to make the haystacks bigger and bigger.

It should be commonsense: larger and larger haystacks only make the needle harder to find. Unfortunately, it's not. And the result is the FBI is collecting more and more data on Americans, which dramatically increases the error and abuse, with significant consequences to innocent Americans' privacy, civil rights, and security.

Learn more about government surveillance and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .