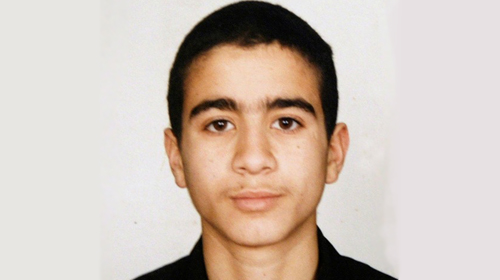

Today marks a decade in U.S. custody for Omar Khadr, a Canadian citizen who is Guantánamo’s youngest prisoner. Even though he has been eligible for transfer back to Canada for almost nine months pursuant to his October 2010 plea deal, he is still detained at Guantánamo. Khadr is the only one of the 168 remaining detainees who was a juvenile when transferred to Guantánamo.

Khadr has grown up at Guant√°namo. Now 25, the full beard Khadr has grown since his imprisonment in 2002 obscures the fact that he was only 15 when he was shot and captured by U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

After his capture, Khadr was taken to Bagram near death: he had been shot twice in the back, blinded by shrapnel, and buried in rubble from a bomb blast. U.S. personnel interrogated him within days, while he was sedated and handcuffed to a stretcher. He was threatened with gang rape and death if he didn‚Äôt cooperate with interrogators. He was hooded and chained with his arms suspended in a cage-like cell, and his primary interrogator was later court-martialed for abuse leading to the death of another detainee. During his subsequent detention at Guant√°namo, Khadr was subjected to the ‚Äúfrequent flyer‚ÄĚ sleep deprivation program and he says he was used as a human mop after he was forced to urinate on himself.

In 2004, Khadr was charged with war crimes in the Guantanamo military commissions, accused of throwing a grenade that killed Sgt. 1st Class Christopher Speer. In October 2010, Khadr , in an 11th-hour plea deal that averted the scheduled resumption of his military commission trial. If Khadr’s trial had gone forward, it would have been the first war crimes prosecution of a child soldier since World War II, and the first ever in U.S. history. Khadr pled guilty in exchange for an eight-year sentence, on top of the eight years he had already served at Guantánamo. Under his plea agreement, after serving one more year, he was eligible to apply to serve out the rest of his sentence in Canada. The arrangement required the assent of the Canadian government and an exchange of diplomatic notes between the U.S. and Canadian governments, which took place immediately before Khadr agreed to the plea deal.

According to his Canadian lawyer, Khadr‚Äôs acceptance of the plea deal was ‚Äúa hellish decision‚ÄĚ in order ‚Äúto get out of Guant√°namo Bay.‚ÄĚ Self-incriminating statements that were coerced out of him by interrogators at Bagram and Gitmo were to be used against him at trial, and his case had been plagued by legal and procedural problems since he was first charged in 2004.

During his decade of detention, Khadr was abused, interrogated more than 100 times, and slated for trial by the discredited military commissions, instead of being held separately from adult detainees and enrolled in education, reintegration and rehabilitation programs as required by international law. Without access to those programs, Khadr told a government-hired psychiatrist that he is studying GED books and textbooks well-wishers have sent him, but has found it difficult to teach himself: ‚ÄúSince I stopped school at eighth grade and it‚Äôs been eight years, some things are hard to learn by myself.‚ÄĚ

Our government‚Äôs treatment of Omar Khadr flies in the face of international law and policy that recognizes child soldiers as victims and candidates for rehabilitation. In contrast, the former Pentagon official who served as chief prosecutor for the U.N. war court convened to prosecute those responsible for wartime atrocities in the 90‚Äôs in Sierra Leone . Although children committed some of the most heinous abuses of the Sierra Leonean civil war, including murder, rape, and amputation of limbs, that war crimes court instead entered these child soldiers in rehabilitation programs and they became witnesses in the war crimes trials against the adults who recruited or used them during the war. Author Ishmael Beah, a former child soldier from Sierra Leone who, like Khadr, was captured when he was 15, has criticized the U.S. government‚Äôs treatment of Khadr. Beah admits that during the civil war he killed ‚Äútoo many people to count,‚ÄĚ but since a stint in a rehabilitation center he has written a , graduated from Oberlin, and served as a UNICEF ambassador. Beah has said he struggles to understand .

Khadr has now been eligible for transfer back to Canada for almost nine months‚ÄĒsince October 31, 2011‚ÄĒbut the Canadian government has yet to request the transfer. Canadian Public Safety Minister Vic Toews has reportedly refused to authorize it, saying Khadr‚Äôs potential threat to Canadians needs to be evaluated. Instead, Khadr has had to turn to the courts in an effort to force the Canadian government to keep the promise it made to let him return to Canada. Last week Khadr‚Äôs lawyers filed a new application asking a Canadian court to order Minister Toews to make a decision.

Canadian Senator Romeo Dallaire recently circulated an to bring Khadr to Canada, which has garnered significant public support. ,

Canada’s role has been a disgrace. Three prime ministers, representing two different political parties and presiding over five different governments, could have taken action. Those prime ministers were served by a total of eight different foreign ministers and five defence ministers, all of whom had the opportunity to do right by Mr. Khadr. None did. Now Mr. Khadr’s fate rests in Mr. Toews’s hands, and still nothing.

Canada must do the right thing. Minister Toews should sign the transfer request and finally put an end to this decade-long debacle by bringing Omar Khadr home from Guant√°namo.

Learn more about children's rights: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .