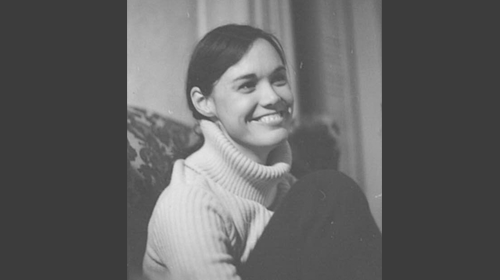

Last week, I publicly revealed my identity as a member of the Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI, a group that in 1971 broke into an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, took documents proving that the FBI had been spying on innocent Americans, and shared them with the public. Since I came forward, I have been repeatedly asked the following: Why would you, a young mother of three, do something so dangerous and with such serious consequences, and put the lives of your children at risk?

I did it because I believe that each of us is responsible for protecting democracy.

Whistleblowers of all generations — from our group in 1971 to Edward Snowden — have gone to great lengths to shine light on illegal and immoral actions, so that "we the people" remain the final arbiters of our democratic values.

I'm now 72. Since my teens, I have been concerned about the protection of people's rights in our democracy. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, I was part of an activist community in Philadelphia, where I joined other progressive souls protesting the war in Vietnam. My husband and I were drawn into what was then called "the Catholic left," using the concept of resistance to disrupt the military draft of mostly poor and working-class very young men.

By creating significant, nonviolent disruptions, like middle-of-the-night raids of draft board offices to destroy files, we were showing — to ourselves and to the public — that the people hold the power in a democracy. For me, these were natural expressions of my responsibility as a citizen.

I felt that responsibility very keenly at that time, when many felt powerless to express dissent. Philadelphia was a center of anti-war activity, and many of us began to fear that J. Edgar Hoover's FBI was using illegal and heavy-handed surveillance and informants to squash dissent. But while we knew this was happening, we also knew it couldn't be proven. Hoover had become so autonomous and powerful no one in Washington or law enforcement could confront him.

So when Bill Davidon, a leader in disarmament and anti-war movements, invited me, my husband, and a few others to consider a raid on a suburban FBI office, I thought the idea was compelling and empowering. A small, tight-knit group with shared values, we understood that Hoover had to be held accountable, and we, the people, had to demand it. We committed to plan and execute the raid and called ourselves "The Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI."

My husband and I and our three children lived in a big old house in Germantown, which became the place where much of the planning happened. We would put our kids to bed, and then go out in teams, casing the FBI office in Media. Then we'd gather upstairs to discuss our plans and observations. Walking past our sleeping kids each night reminded me of how serious the consequences could be for me and for my family if we were caught. But it also reinforced my decision: I felt I had to do everything I could to create the kind of country I wanted my children to grow up in.

After months of casing and planning, we had almost everything we needed: we were familiar with the building, the neighborhood, and the movements of the agents and guards; we had a clear idea of our plan for the night of the raid; and one of our members, Keith Forsyth, had trained himself as a locksmith so that he could pick the lock on the office door. To obtain a better picture of the inside of the office, I posed as a college student researching career opportunities for women in the FBI. I made an appointment to interview the office head, and disguised my appearance with a floppy hat, big glasses, and gloves. During my meeting, as I chatted politely about FBI jobs for women, I made a mental map of the office: rooms, file cabinets, doors, furnishings. Most importantly, I had to pay close attention to see if there were any security alarms or locks on the file cabinets.

Amazingly, there were none. My scouting was the final piece of the puzzle. That's when we made the decision to move ahead. On the night of March 8, 1971, while Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier made television history with the "fight of a century," our team put our plan into action.

Keith picked the lock and we entered the office, removed every file, and loaded them all into suitcases. Then we walked out the front door.

When we reached our rendezvous point, we began sorting through the documents, looking for evidence of the FBI's wrongdoing. We found out what we had feared – a secret, massive FBI system of domestic surveillance and intimidation. We shared those documents with the press, and, in turn, with the American people. That revelation led to hearings and to greater oversight over the intelligence agencies.

With our mission accomplished, we quietly went back to our day-to-day lives. And, over the past 43 years, as our kids grew older (and we did too), reflecting on that period of my life, the risks and the rewards, I know I couldn't have made any other decision. Just because we were parents didn't mean we could shake off our responsibility as citizens. It's a responsibility we all share.

Learn more about government surveillance and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .