This piece originally appeared at .

The Senate report released earlier this week makes clear that the CIA tortured more men, and far more brutally, than anyone outside the intelligence community previously understood. Given the report's findings, the attorney general should appoint a special prosecutor who can conduct a comprehensive criminal investigation.

The argument for the appointment of a special prosecutor is straightforward. The CIA adopted interrogation methods that have long been understood to constitute torture. Those methods were used against more than a hundred prisoners, including many – at least 29 – whom the CIA itself now recognizes should never have been detained at all.

The methods were extreme, even grotesque. One prisoner, known as Abu Zubaydah, was slammed against walls, stripped naked, hung from his wrists, and waterboarded 83 times, once to the point of unconsciousness. Over the course of 20 days, he spent more than 11 days in a "confinement box" made to look like a coffin and another day and a half in a box that was, by design, too small to allow him to straighten his legs or his back. Abu Zubaydah's interrogators set out to destroy him physically and mentally, and they did.

But Abu Zubaydah's experience was unique only in its particulars. The CIA used the same methods against many other prisoners. A CIA interrogator observed that prisoners at one of the agency's black sites "looked literally like dogs who had been kenneled."

At a news conference on Thursday, the CIA's director, John Brennan, conceded that there is no evidence that the use of "enhanced interrogation methods" (as he called them) yielded more evidence than lawful methods would have.

But the more important point is that the use of these methods was a crime. It was a violation of the federal torture statute, which prohibits the intentional infliction of severe physical or mental pain or suffering. It was a violation of the War Crimes Act, which criminalizes grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions.

And it was a violation of the most fundamental human rights norms. The Convention Against Torture, which President Reagan signed for the United States in 1988, prohibits torture as well as cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. Under international law, the torturer is considered hostis humani generis, the enemy of all mankind.

"How will we encourage other nations to treat their prisoners with dignity when we have treated ours with such cruelty?"

If we don't hold our officials accountable for having authorized such conduct, we become complicit in it. The prisoners were tortured in our names. Now that the torture has been exposed in such detail, our failure to act would signify a kind of tacit approval. Our government routinely imprisons people for far lesser offenses. What justification could possibly be offered for exempting the high officials who authorized the severest crimes?

And our tacit approval of torture, besides calling into question our commitment to our laws and our values, would fatally compromise the United States' ability to advocate for human rights abroad. How will we encourage other nations to treat their prisoners with dignity when we have treated ours with such cruelty?

If we fail to hold accountable the people who authorized torture, we also invite future administrations to resurrect the policies that the Obama administration has retired. At Thursday's press conference, Brennan said the question of whether to use torture was a question of policy – not law – to be decided by policymakers. If we don't enforce the laws against torture, Brennan will turn out to be right.

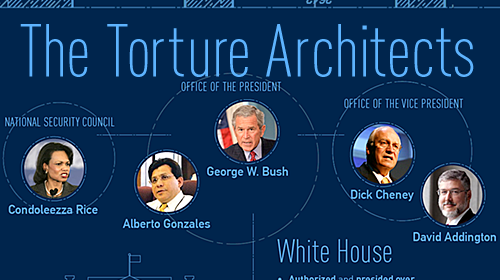

The notion that future administrations may resurrect the torture policies surely isn't fantastical, when former officials – including Vice President Dick Cheney – continue to say that torture was effective and necessary, and when the current CIA director refuses even to acknowledge that the torture methods were in fact torture.

And let's be clear: The danger isn't simply that some future administration will revive the methods that the Senate report discredits. The larger danger is that our failure to hold accountable the people who authorized torture will send the message that any conduct, however unlawful and abhorrent, will be excused if it is executed in the name of national security. If we fail to hold accountable the torturers, we risk entrenching the dangerous view that the intelligence agencies responsible for protecting the nation's security are beyond the reach of the law.

Those who oppose the appointment of a special prosecutor argue that the Justice Department has already investigated the torture of prisoners. But the Justice Department apparently focused on instances in which interrogators overstepped limits set by senior officials, rather than on the culpability of senior officials themselves. Media organizations and human rights groups have asked the Justice Department to explain how it could possibly have concluded that no government official should be prosecuted for the abuse and torture of prisoners, but thus far it has declined to respond.

The attorney general should appoint a special prosecutor. For the last decade, officials who authorized torture have been shielded from accountability for their acts. The Senate report makes it clear – indeed, it could not make it any clearer – that impunity for torture must now come to an end.

Learn more about torture and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .