How Broadband Access Advances Systemic Equality

If youÔÇÖre reading this article, youÔÇÖre probably not one of the of people living without broadband access in America. People living without broadband access ÔÇö who are disproportionately non-white people, low income, or rural ÔÇö do not have access to equal opportunities in education, employment, banking, and other important components of connection and social mobility. That was the case before the pandemic, and itÔÇÖs even worse now.

The digital divide is what separates those without broadband from those with it, and it encompasses all the broader social inequalities associated with an increasingly digitized world. Along with discrimination in housing, banking, employment, and other areas of life, it is both a result of and contributes to systemic inequalities faced by people who are Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and other underserved groups.

What is broadband and why do we need it?

Broadband is the term used to describe high-speed, reliable internet ÔÇö the kind of internet that allows us to stream movies, take part in Zoom calls, and connect with our social networks. Since , the Federal Communications Commission has defined broadband as a minimum of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) download and 3 Mbps upload. But while internet upload and download speeds have changed significantly over the years, the FCC has not updated its definition. That makes it difficult to get an accurate picture of how many people are living without access to the internet thatÔÇÖs usable given todayÔÇÖs higher technology demands.

Over the past year, schools, workplaces, health care providers, and many other basic services and functions have moved online, allowing for life to continue during lockdown. The numbers reflect this societal shift: Data use on home networks was in March 2020 than the year before. But as broadband has become even more integral to our everyday lives, not all communities have had equal access. For communities living without broadband, the pandemic has only exposed and exacerbated the digital divide.

How does broadband contribute to systemic equality?

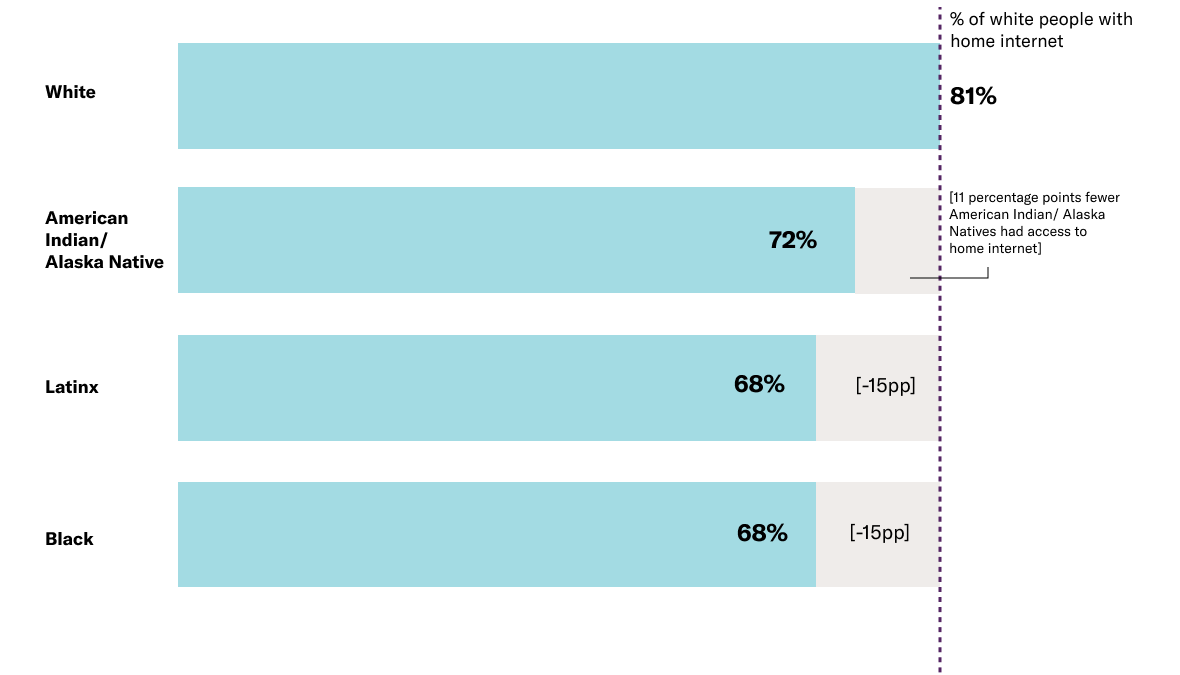

The deepest rift in the digital divide is when it comes to race: Black and Latinx adults are almost twice as likely as white adults to lack broadband access. Due to systemic inequities in education and employment, people who are Black or Latinx have lower average incomes than white people, and for many of these households, a broadband subscription ÔÇö at an average rate of per month ÔÇö may simply be unaffordable.

Check out the chart below for a rough monthly estimate for a family of four (two adults and two minors) living in Washington, D.C, a historically . At about $6,515 per month, the estimated monthly expenses amount to over $2,000 more than the median individual monthly income, to U.S. Census Bureau data from 2019. Even in a household with two income earners, there is almost no room for any unexpected expenses.

Adults living without broadband face significant barriers in accessing employment, education, and other necessities ÔÇö but children are also impacted. Access at home is an important factor in a , and is associated with higher grades and homework completion. This need was amplified by the pandemic. Many of the millions of Black and Latinx children who live in households without broadband access have not been able to attend virtual classes, potentially falling behind their classmates by an entire school year or more.

Children without broadband also miss out on developing digital skills that are necessary in todayÔÇÖs job market. As a result of the digital divide, of Black and Latinx people could be under-prepared for 86 percent of jobs by 2045, according to Deutsche Bank. These digital skills are also crucial to innovation and entrepreneurship. Black-owned businesses have increased . The 2019 American Express State of Women-Owned Businesses Report shows that Black women-owned businesses are the fastest growing at 21 percent of all women-owned businesses but only have an average annual earning of $24,000. Limited broadband access compounds the numerous systemic inequity barriers to Black-owned and Black-women owned business growth.

Access to home broadband by race

Source: analysis of July 2015 Current Population Survey Computer and Internet Use Supplement

The systemic inequity posed by limited broadband dovetails with a science policy concept called ÔÇ£public value failure.ÔÇØ describe the failure of a society to provide a public value, such as rights, benefits, or privileges of citizens provided by governments and policies. There are nine public value failure categories, which cover the political, economic and social aspects of this theory: mechanism for values articulation and aggregation; legitimate monopolies; imperfect public information; distribution of benefits; provider availability; time horizon; sustainability vs. conservation; and ensuring subsistence, human dignity, and progressive opportunity.

Focusing on all of these public failures simultaneously wonÔÇÖt lead to substantive and sustainable change. So, we tackle what we can. Broadband access falls most fully into the distribution of benefits and provider availability categories, with arguably a large dose of the progressive opportunity category as well. All of our classrooms ÔÇö regardless of a personÔÇÖs socio-economic status, urban/rural location, or in-person/remote delivery ÔÇö require broadband access to hear an instructorÔÇÖs lecture, see a helpful tutorial, and practice the new skill. Identifying and improving in these areas hinges on building better equity in education, particularly in .

How do we bridge the digital divide?

There are steps the government can and must take to expand broadband access to Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and other underserved communities. In Congress, new legislation introduced by Rep. Jim Clyburn, the , would help sustain equitable broadband access by providing an additional $6 billion in funds for the Emergency Broadband Benefit, an FCC program created to help households struggling to afford broadband during the pandemic. The legislation would also improve data collection and transparency on broadband access, expand digital inclusion and equity efforts, preempt state laws that prevent municipalities from expanding broadband access, and prioritize infrastructure deployment to unserved areas, such as Tribal lands.

At the executive level, President Biden has already taken important steps by in his American Jobs Plan, but he can do more. Biden must also nominate a new FCC commissioner who supports broadband access and will restore net neutrality protections, and work with Congress to enact sustainable solutions to close the digital divide.