Racism by Design: The Building of Interstate 81

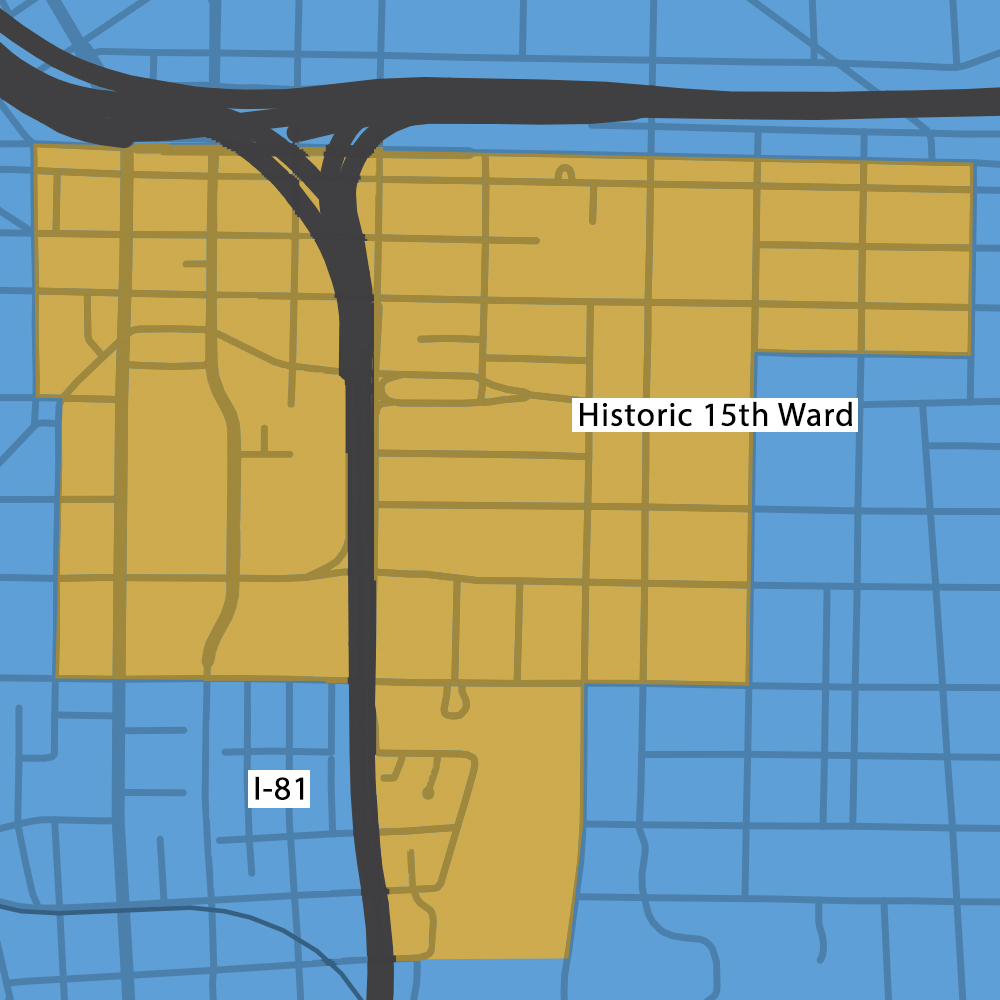

David Rufus was just a toddler when the bulldozers rolled into the streets of his Syracuse, New York, neighborhood in 1960. As part of the country’s interstate highways surge, city officials wanted to extend I-81 with an elevated viaduct that would cut right through the 15th Ward, where nearly 90 percent of Syracuse’s Black population lived. Protesting locals were ignored, and the razing of homes, churches, and businesses resulted in the displacement of more than 1,300 families, including Rufus’s. Over the next 50 years, the 15th Ward community suffered in every way possible—jobs, housing, schools, and public health plunged while crime, pollution, and poverty spiked.

“I’ve lived in this community all my 64 years,” says Rufus, who’s lost several family members to respiratory illness. “I’ve seen the move from a very vibrant and interactive community of people of color to a community that has been shunned and overlooked and broken down.” The I-81 project was completed in 1968—and Syracuse remains one of the most segregated cities in the country, with the highest concentration of poverty among communities of color and one of the highest rates of lead poisoning in children. The viaduct still physically separates the poorest and wealthiest communities, and the city’s Black population has been harmed for generations.

This was by design.

After the mid-century extension of I-81 in Syracuse, more than 1,300 families in the 15th Ward were displaced, and a vibrant Black community was destroyed.

The interstate highway system birthed by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 was the largest public works program the country had ever embarked upon. More than 40,000 miles of highway were planned and built steadily through the ’60s and ’70s as a driver of economic progress. As the civil rights movement was gaining momentum, the highway system became a way to enforce segregation through other, quite literal, means. So-called slum clearance destroyed under-resourced but thriving working-class Black neighborhoods while enhancing the flow of white commutes and tax dollars to the suburbs. Communities of color were cut off from developing downtown centers, and not just freeways but also refineries, landfills, and power plants were dumped in non-white areas labeled “sacrifice communities.”

Now many of these highways are crumbling, and cities are weighing how to repair, revamp, or remove them. For racial justice advocates, these looming infrastructure projects are a crucial opportunity to redress the historical discrimination built into them. The I-81 in Syracuse, which is failing, has become the highest-profile example of the potential to undo this damage and create a new model for reconnecting shattered communities with equitable resources. The ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű’s New York affiliate, the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU), has been advocating for a decade to ensure that this time the community has a voice in what happens. The NYCLU’s 2020 report, “,” has been instrumental in pushing the city’s plans in a more just direction that takes a reparative approach.

A lot is riding on the effort, as wrongheaded plans would simply reinforce the historical damage or encourage gentrification that displaces the neighborhood’s residents yet again. No one understands the stakes better than Rufus, now the NYCLU’s dedicated I-81 community organizer. “If I-81 is a successful project, and it provides the kind of rebuilding of wealth and community that is so necessary, it could become a blueprint for the state and for the country,” he says. “Justice elements like the ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű and NYCLU have to make sure that the tools the federal government gives [us] aren’t used as assault weapons against the neighborhood.”

When most of us think of racial injustice, interstate highway design isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. It is, in fact, a perfect example of structural racism in action: intentional government policy, enacted in almost every city in the country, that damaged every aspect of Black lives—cultural, economic, environmental, educational—for generations.

“The Monster.” That’s what some residents of Tremé and the 7th Ward of New Orleans call the Claiborne Expressway, the I-10 overpass that demolished the neighborhood in 1968. West Baltimore residents named theirs—State Route 40—the “Road to Nowhere.” Interstate-20 in Atlanta. I-579 in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. I-94 that bisected the Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota. I-375 that crushed Black Bottom and Paradise Valley in Detroit. I-95 that wrecked Miami’s Overtown neighborhood, known then as the “Harlem of the South.” I-65 and I-85 in Montgomery, Alabama, rerouted through Centennial Hill, Bel Air, and the Bottoms as retaliation for civil rights activity (Revs. Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy lived there). The examples are endless.

The ripple effects of these highway projects were immediate and far-reaching, the cumulative devastation staggering. No aspect of neighborhood life and culture went untouched. Healthy food became scarce. Businesses failed. Job opportunities diminished. The housing market cratered. Pollution—noise and environmental—spread: rates of illness, particularly asthma, rose dramatically in those neighborhoods crammed against (and sometimes under) the freeways and overpasses.

Articles from the time abound with efforts to stop the projects. But it was the same story every time: The community was not asked for input and held no political power. This was adding insult to injury since many of these majority-Black neighborhoods had sprung up in the first place because of redlining and Jim Crow segregation. While they often became vibrant, self-contained enclaves, the fact that they were under-invested and overcrowded was subsequently used as rationale for destroying them. One of the most devastating effects has been how these inequities have reinforced the racial wealth gap.

“These big concrete barriers further concentrated race and poverty, coupled with redlining, where folks were unfairly denied mortgages or more affordable lines of credit to invest in their communities,” says Carlos Moreno, a senior campaign strategist who leads the ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű’s Systemic Equality agenda to address America’s legacy of racism through advocacy and litigation. “The first avenue for wealth is buying a first home and having it appreciate. Homes in redlined communities typically do not appreciate, and they are subject to nefarious slumlords and all sorts of ugly things.”

And it’s still happening. Charleston County, South Carolina, is considering a $3 billion proposal to expand a West I-526 interchange that would demolish or move close to 100 mostly Black- and Brown-owned businesses and homes in neighborhoods of North Charleston. Pressure from local groups, including the ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű of South Carolina, forced the county to revise a separate plan to widen Highway 41 so that it will do a better job of minimizing the impact on Mount Pleasant’s historic Phillips Community, one of the last remaining Black settlement communities in the region.

“These types of projects upset the ecosystem,” says Helen Mrema, community organizing advocate at the ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű of South Carolina, one of 12 ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű affiliates that make up the Southern Collective, an initiative to increase Black political power and representation in the South. “They force residents to move and figure out how to tap back into resources that are now even more difficult to access. It creates a targeted community that is essentially set up to fail.”

The Central New York chapter of the NYCLU was born in the spring of 1963 as a direct result of the police harassment and arrest of 15th Ward residents protesting the destruction of their neighborhood for the I-81 viaduct. And now the community has another chance to influence the highway’s reconstruction and reimagining.

“What we do is try to empower and reactivate the community,” says Lanessa Owens-Chaplin, director of the NYCLU’s Racial Justice Center. “Because they lost that fight. So how can we convince them that maybe we can win this one? In the ’50s and ’60s, we didn’t have many protections. Now it’s a different fight.”

In recent years, more people and high-level institutions have acknowledged the structural racism built into the country’s highway system. ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű National Board President Deborah Archer is one of the leading national scholars on the issue. Her seminal Vanderbilt Law Review piece, “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction,” established transportation policy as a civil rights issue, and her work has laid the constitutional and policy framework for remedying these injustices. Archer has advised Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, who in April 2021, acknowledged publicly that the “racism physically built into some of our highways” was a “conscious choice.” And while grassroots organizers and environmental justice groups have long been calling attention to the devastating damage highway planning inflicted on communities of color, the Biden administration’s inclusion of the issue in the $1.2 trillion infrastructure plan signed in November has opened the door for more organizations to take on this type of work. Calling out I-81 and the Claiborne Expressway in particular, the plan earmarks $1 billion for a new program called Reconnecting Communities that “will reconnect neighborhoods cut off by historic investments and ensure new projects increase opportunity [and] advance racial equity and environmental justice.”

“The infrastructure plan gives it more bite,” says Owens-Chaplin. “State governments are not only being held accountable by their community, now we have the administration calling for this kind of restorative justice. New York state can be a great example if we can get them to think outside the scope of just laying slabs of concrete down and really start thinking about restoring the community.”

The NYCLU, which had dedicated additional resources and staff to the I-81 project in 2018, incorporated voluminous feedback from the community to outline a vision for the revitalization project that this time honors the people’s needs. It urged the New York State Department of Transportation to transfer any developable land to a community land trust controlled by the residents, maintain meaningful economic and environmental safeguards for those living along the viaduct during and after construction, and take a reparative approach that works to close the wealth gap and reconnect fragmented parts of the community.

Additionally, along with coalition partners CNY Solidarity Coalition and Urban Jobs Task Force, the NYCLU has pressured NYSDOT and local trade unions to commit to racial equity in hiring so that local community workers benefit from the thousands of construction jobs created by the I-81 project. Meanwhile, Rufus helps residents understand their rights and contribute their voices to the process, liaising with the DOT, the Board of Education, the mayor’s office, and the Syracuse Common Council. “Three years ago,” says Owens-Chaplin, “DOT wasn’t talking about equity or restorative justice or how can we repair the community. Today, they are talking about it. So there is progress.”

The draft environmental impact statement NYSDOT released in July included key changes to the preferred community-grid version of the I-81 revamp. Air-quality monitoring systems will now be placed around houses nearest the construction. And, of key importance, a land use working group will be created so that local leaders and residents have a prominent voice in making sure the 10 to12 acres freed up by the viaduct’s removal are used in a way that benefits the existing community, whether through local business development, affordable housing, or usable green spaces.

Last September, a group largely composed of white suburban residents known as “Renew 81 For All” filed a legal challenge against NYSDOT, attempting to halt the development of this preferred community-grid option and advocating for a larger highway instead. NYCLU filed an amicus brief against the group's challenge, and the case is currently up for appeal in the state’s 4th department.

“The biggest point of the effort is holding the government accountable,” says Owens-Chaplin. “That’s what the big fight is here in Syracuse. It’s easy for them now, 60 years later, to recognize the damage they’ve done, but they’re still not doing what they need to do to restore the community.”

The generational setbacks of these highway decisions still resonate today, compounding over time to exacerbate the racial wealth gap and withhold the American dream from too many communities of color. Closing this gap is a major goal of the ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű’s Systemic Equality campaign, since comprehensive reparations are the only way to repair the historic inequality driven by racist policies, a lack of job opportunities, and depressed home ownership.

“Redressing harm could take the form of providing proper housing, investing in communities through grants for businesses, or passing baby bonds legislation to give folks assets,” says Moreno. “Because when we’re talking about closing the racial wealth gap, we’re not necessarily talking about income. What we’re really talking about is wealth. The main focus with systemic equality is to find an innovative set of tools or programs that provide immediate material relief for Black communities living in poverty.”

The potential for transformation is national in scope: Right now, nearly 30 cities have plans in the works to repair crumbling urban highways. They could prioritize reparative justice by taking cues from the NYCLU’s I-81 proposal: protect future land use so that residents of the affected community have preference in any development; create a community restoration fund to eliminate environmental hazards and compensate those whose health and wealth have been negatively impacted; devote revenue generated from community development to increase school funding in an equitable manner that redresses long-standing underfunding; and provide hotel vouchers, market-rate buyouts, rent subsidies, and/or temporary relocation assistance to those households most likely to be impacted by construction, along with automatic right of return when the construction ends.

The NYCLU’s campaign on the I-81 viaduct is crucial to establishing a template for how these projects can actively address systemic injustice and knit these communities back together. The bottom line is for careful planning to ensure that “people who have lived their lives in the neighborhood are able to stay, engage equitably in the rejuvenation of the community, and begin to build wealth.”

“It’s important for the ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű to be taking on these issues because it really is an issue of civil rights and racial justice,” says Owens-Chaplin. “We need to make sure that everyone has power over government decision-making and make sure everyone’s rights are preserved and protected.”

“This is an opportunity for the country to get it right this time,” says Rufus. “When they designed I-81, they just drew it with a black pen. They didn’t stop to take the time to see if that black line ran over a person’s house or a person’s head—or a person’s heart.”

This article originally appeared in the ŔĎ°ÄĂĹżŞ˝±˝áąű magazine. Join us to receive the next issue. The article has been updated to include litigation developments that occurred following its publication in the magazine.