In her heartfelt dissent in Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, which upheld a Michigan ballot initiative forbidding schools from considering race as one factor in admitting students, Justice Sonya Sotomayor wrote "the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race."

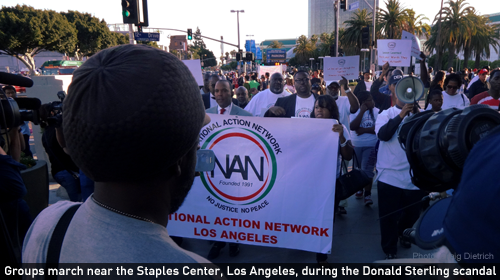

Days following the momentous case, the nation was embroiled in discussions of race sparked by statements made by Los Angeles Clippers owner and Nevada rancher .

Although the discussions captured the nation's attention, they were probably not what Sotomayor had in mind. These conversations are ultimately empty because they did little or nothing to illuminate the problems of discrimination today.

Both men made statements that confirmed William Faulkner's observation that "the past isn't dead...[i]t isn't even past." Resurrecting offensive stereotypes, Sterling was quoted as warning his multi-racial girlfriend against being seen publicly with black people, while Bundy waxed nostalgically about all the benefits supposedly enjoyed by black people under slavery.

Both men seem like caricatures of the historical racist.

Few things are more deeply rooted in American history than a person espousing virulent racism in spite of the fact that he is financially dependent on the labor of blacks and is intimately involved with a person of color. Bundy's depiction of slavery, owing more to "Birth of a Nation" than "12 Years a Slave," rehashes the offensive depictions of the antebellum South used to justify discrimination beginning soon after the Civil War.

Both men earned the condemnation that was heaped upon them. But we are mistaken if we pat ourselves on the back for taking the two men to task. In truth, the discussions were more of a sideshow that failed to address the real problems of modern racial inequality. We still have not taken the necessary steps to have the discussion which Justice Sotomayor urged upon us.

That discussion would have been better served by considering a study which received far less attention.

In the study, "," law firm partners were asked to evaluate on a five-point scale a single memo into which errors were deliberately inserted. Half of the partners were told that the author of the memo was African-American, while the other half were told that the author was white. The partners reviewing the memo that they thought was written by a white person rated it at 4.1 while scoring the exact same memo 3.2 when they believed it was written by a black person.

Most striking was the extent to which the partners were swayed by the believed race of the author. They only found an average of 2.9 errors for the believed white author as opposed to 5.8 for the believed black author, even though the mistakes inserted into the writing sample were totally objective errors, like misspelled words and errors of grammar.

Far from being color blind, these partners were quite literally blinded by color. Their expectations, whether conscious or unconscious, were so strong that they actually failed to see mistakes by people whom they thought to be white.

The partners in the study were probably nothing like Sterling or Bundy. They undoubtedly pride themselves on their fairness and impartiality. But the study demonstrates the powerful effect that prejudice, even when it is unconscious, can have ÔÇô an effect only magnified by the power wielded by the partners.

Not only do they make decisions regarding their law firms, but they are emblematic of the people who make life-changing decisions, such as who is admitted to a school, who is hired, or who receives a mortgage and on what terms. These people are gatekeepers to opportunity, and the effect that race continues to exert is the real problem we all face.

We need to condemn those who make outrageous statements but, more importantly, we need to look deep within ourselves to find the deeper roots of inequality.

Learn more about racial discrimination and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .