At a time of rising anti-Muslim rhetoric and discrimination, communities nationwide are coming together to push back. This is the third in a series of blog posts meant to highlight this fight for equality and religious freedom.

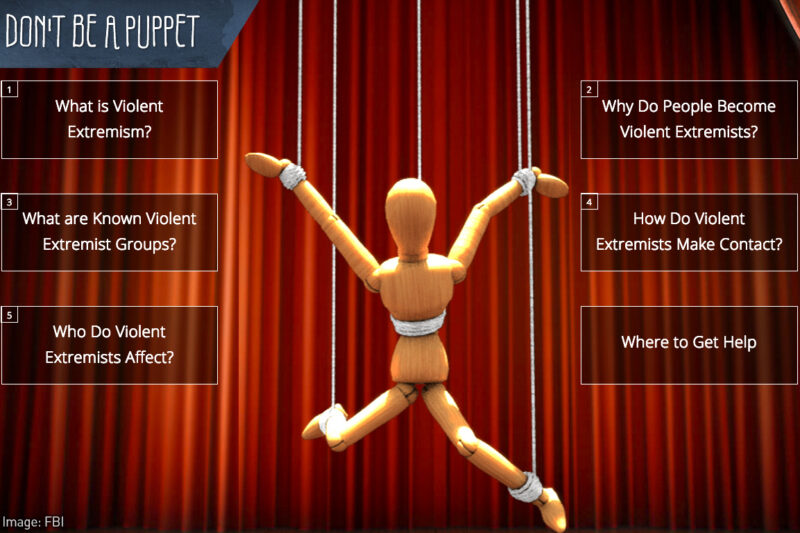

Earlier this month, the FBI quietly launched “Don’t be a Puppet,” a website aimed at teachers and students, ostensibly to teach them how to spot and counter the “radicalization” of young people. It wasn’t a hit. One tech writer called it an “.” Another headline read, “.”

From the , players set off through five stages: What is Violent Extremism? What are Known Violent Extremist Groups? Who Do Violent Extremists Affect? Why Do People Become Violent Extremists? How Do Violent Extremists Make Contact? As players successfully answer questions, they get to cut the puppet strings and ultimately earn an “FBI certificate” upon completion.

If the problem were simply bad execution it might be enough to laugh the effort off as out-of-touch bureaucrats attempting to connect with teenagers. But “Don’t be a Puppet” is hardly innocuous. It represents some of the worst elements of the federal government’s “Countering Violent Extremism” (CVE) initiative, which targets entire Muslim communities for what it terms any signs of “radicalism” — violent or otherwise.

Formal CVE programs have so far only been in Muslim communities in Boston, Los Angeles, and the Twin Cities. But CVE-based policy can be found in many places — including this FBI video game.

Officials say CVE programs are meant to identify and prevent people, especially young people, from becoming violent extremists. In reality, CVE is based on the flawed idea that there is a typical path a person takes to become a terrorist. Further, CVE tasks community members — particularly Muslim community members — with monitoring each other, stirring suspicion within a community that is already feared and discriminated against from the outside.

As from the civil rights community grows, federal officials insist CVE doesn’t single out Muslims. It’s true that they use careful language to ward off these complaints and occasionally point to white, right-wing extremist violence. But no other group is targeted, or for crimes of a few, by the government in the same way as the Muslim community.

It doesn’t help that the government’s justification for CVE mirrors that of explicit anti-Muslim activists, including the grassroots “national security” group . The group and its leader, , want to convince the public and public officials that the threat posed by Muslims is not necessarily violence, but a cultural takeover. The group has lobbied to and other religious practices and is to in the United States. Gabriel is an unabashed critic of Muslims who “every practicing Muslim is a radical Muslim” a “Muslim who goes to the mosque...who prays five times a day” cannot be a “loyal citizen of the United States.”

ACT! for America, which boasts more than 800 chapters and 300,000 members in the United States, recently sent an email to its supporters to empower them to spot radicalization. As part of its “” campaign, the email lists what to watch for: A person with a sudden “insistence on religious ritual,” who adopts “traditional Arab dress or abruptly abandon(s) it,” who “expresses increasingly angry and disillusioned views about America, our policies or society,” and so on. “Identifying suspicious activity is not a difficult science,” the email reads, without irony.

Disturbingly, federal and state law enforcement agencies use many of the same “radicalization” identifiers named by ACT!. For example, the , , and ACT! for America have all identified “isolation” is a key sign on the road to radicalization. Other “signs” shared by all three entities include foreign travel, increased political activity, and change in attire — all lawful activities that now exist in a “pre-criminal” purgatory.

“Don’t be a Puppet” was scheduled to go live in November, but the FBI put the launch on hold after , again calling out the disproportionate emphasis on Muslims. Advocates argued that even more discrimination and bullying could come from the game’s suggestion that and other religious and cultural identifiers are linked with a propensity for violence.

Then, on February 8, without fanfare or press coverage, the FBI published the site and issued a on its website reading, “The program encourages teens to think for themselves and display a healthy skepticism if they come across anyone who appears to be advocating extremist violence.”

Anyone who encounters this program should be encouraged to maintain a healthy skepticism of any of the claims it makes.

How can this game — or the CVE program as a whole — truly urge teens to “think for themselves” when it reinforces about what causes extremist violence? Does the government really want us to cast suspicion on innocuous activities like praying, growing a beard, attending places of worship, traveling, and expressing political beliefs? If so, who is pulling whose strings here?

Read the previous posts in this series:

I Am a Muslim American Army Reservist Who Was Turned Away From a Gun Range Because of My Faith