It should outrage us that a homeless man will be in prison for the rest of his life because he was the . We can all pretty much agree that the punishment of growing old and dying behind bars for such offenses is a wildly extreme, tragic and wasteful overreaction to the crime.

But it should not surprise us. are just the tip of the iceberg.

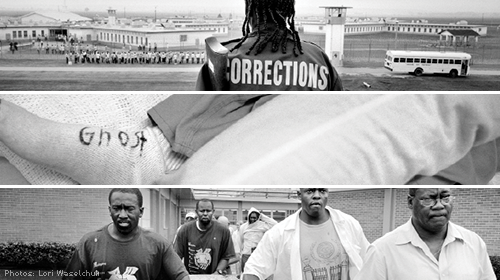

Hundreds of thousands of people in American prisons are serving decades-long sentences that are far out of proportion to their crimes. They comprise an increasingly aging prison population that costs more and more to maintain as their health deteriorates, increasingly strapping state budgets. In many cases, the person incarcerated could have been effectively held accountable in the community with no prison time at all. In other more serious cases where incarceration may be warranted, the person incarcerated could successfully return to the community after a much shorter time in prison, especially if job training and education were available to ease reentry. But this is not the norm.

Instead, in jurisdictions all around the country, incarceration has been touted as the solution to scores of problems it is ill equipped to address, pushing the number of people in jail and prison to over 2.3 million people. That's more than the number of people living in New Mexico. This prison-focused punishment system is wildly expensive, destructive to families and communities, and does not work. Research shows тАФthe longer a person is incapacitated and removed from family and work opportunities, the less bang we get for the buck in terms of reduced recidivism.

Many policy makers agree that sentencing law relics of the 1980's and 1990's are ineffective. So what stands in our way? For too many Americans, the long sentences we mete out are just the "new normal." It is hard to shock us when it comes to our criminal justice system. The ease with which we throw away certain people's lives, particularly the lives of black and brown men, women, and children, demonstrates a general disregard and devaluation of certain communities as irredeemable and unworthy of meaningful interventions that might actually change the course of their lives and heal their communities, and to which many other communities have easier access.

Much of the extreme sentencing in America is justified in the name of victims, with the aim of preventing violence and keeping communities safe. The irony and the lesser known fact is that the majority of crime victims in this country come from the same high incarceration communities. Moreover, have found that the vast majority do not want the people responsible for hurting them to be incarcerated if alternatives are available. What matters most to victims of crime is that what happened to them not happen to anyone else. They see the sky-high recidivism rates, and recognize that long prison terms are doing a terrible job of ensuring that people don't commit crimes in the future. If our goal is to promote safe and healthy communities, we need a different strategy, one that promotes real solutions, such as robust, community-based programs that provide job training, education, classes, and other accountability measures to people who have committed crimes.

There's a saying that a rising tide lifts all boats. The same is true of our national obsession with extreme sentencing. The 3,278 people profiled in the └╧░─├┼┐к╜▒╜с╣√'s recently-released report, , were convicted of relatively minor drug and property crimes. And yet even they received sentences at the extreme end of the spectrum: life without parole. It is time to hold our system accountable for its actions.

We can do better. We know that extreme sentencing is not the answer. Help us fight it at .

The complete report A Living Death: Life without Parole for Nonviolent Offenses is available .

Read some of the stories of people serving life without parole on our .

Learn more about extreme sentencing and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, , and .